We’re Living in an “Anti-Future” World. How Can We Change It?

Commentary by Carolyn Raffensperger

Climate change has altered our sense of time, much the way the astronauts’ glimpse of our beautiful, blue planet changed how we saw space. The future looms large. And to many, frightening. Thousands, if not millions, of people are racing against time to salvage enough so we have a livable future.

Where are the plans, the blueprints, the maps to that future? Readers of Kim Stanley Robinson’s new novel, The Ministry for the Future will gleefully answer, “in fiction!”

Adrienne Marie Brown said that “all organizing is science fiction . we are bending the future, together, into something we have never experienced. a world where everyone experiences abundance, access, pleasure, human rights, dignity, freedom, transformative justice, peace. we long for this, we believe it is possible.”

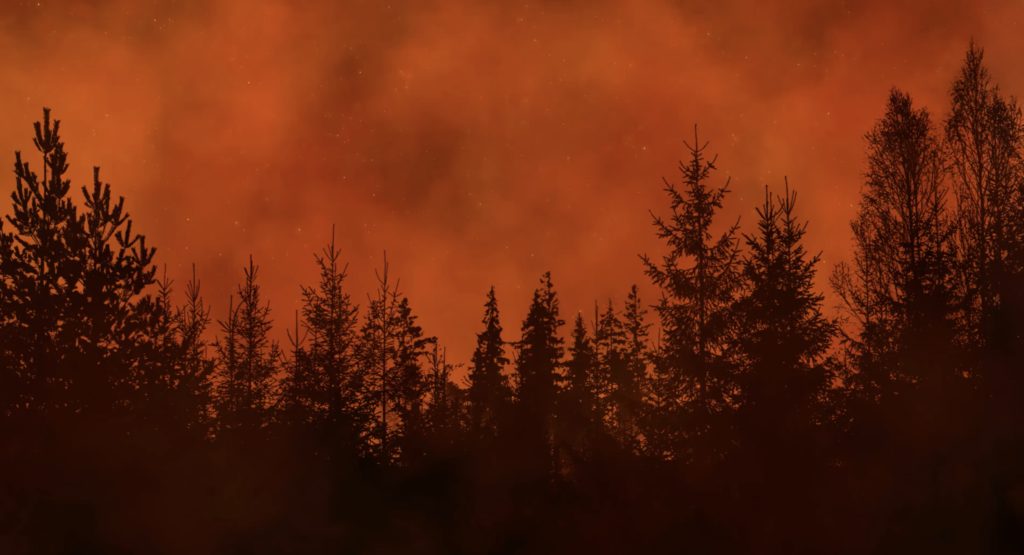

The Ministry for the Future “… opens like a slow-motion disaster movie . In the near future, a heatwave of unsurvivable “wet-bulb” temperatures (factoring in humidity) in a small Indian town kills nearly all its inhabitants in a week…” Out of the wreckage of that climate disaster the world comes together and creates an international body “charged with defending all living creatures present and future who cannot speak for themselves”. The Ministry for the Future.

What is so striking about this fictional account of climate change is that it is spun out of the existing economic and policy systems that are anti-future. By anti-future, I mean the things that support the free market at the expense of the Earth and all living beings (think: slow-motion disaster movie). He carefully dissects these policies and shows us how to create a pro-future world.

At SEHN we’ve spent almost two decades working to design and implement policies that would give future generations a sporting chance. From creating legislative and constitutional provisions for a legal guardian for future generations to advocating for the equivalent of a Ministry for the Future at the U.N ., we’ve invented new institutions that meet the challenges of our day. Robinson’s book captured all the roadblocks we ran into and shows us how they might be dismantled.

For example, one of those road blocks is the Gross Domestic Product (GDP). The GDP is one measure of the success of government. Robinson says the GDP “consists of a combination of consumption, plus private investments, plus government spending, plus exports-minus-imports.” (pg 75) The problem of the GDP is what it leaves out and what it includes. For instance, lots of negative things are factored into the GDP that should actually be counted against the GDP. The medical care costs for your cancer caused by pollution add to the GDP even though those costs, should be considered a debt, a loss.

Robinson lists alternatives to the GDP that have been proposed by various governments and institutions: The Genuine Progress Indicator, the U.N.’s Human Development Index, the Happy Planet Index, the Ecological Footprint and Bhutan’s Gross National Happiness.

So why do we keep using a metric like the GDP that only measures economic success and not real well-being?

The answer is fairly simple. If all we are asking of government is to grow the economy (and stay out of the way of the market), then we will measure government’s success through economic measures like the GDP. But if we recognize government’s real responsibility to, say, foster well-being and protect the commons (air, water, airwaves, parks, public health) then other measures will fit better and are more likely to be adopted.

At SEHN with the Bold ReThink, we are building on our future generations work by focusing on the role of government as guarantor of well-being, grounded in protection of the commons.

In past issues of the Networker we showed how different theories of government resulted in remarkably different approaches to state budgets. If you think government is by and for the economy, then you give taxpayers’ money to big corporations as tax credits and tax incentives . You privatize Medicaid or parking meters and you starve public institutions like the Post Office and neglect to clean up dirty water . And you use the GDP to measure success.

The first thing a more accurate measure of government success would do is shape public spending . If the legislature and executive branches are assessed by whether the water is drinkable, the suicide and cancer rates have gone down and more students actually graduate high school, you are going to spend money on those goals.

There are some wonderful experiments going on with public money. For instance New Zealand has created a Well-Being agenda and corresponding budget. These are pro-future policies.

Robinson’s novel makes a compelling case that our old ways of governance are pitching us headlong into trouble. As Bill Mckibben says , “We are lucky to have a writer as knowledgeable, as sensible, and as humane as Robinson to act as a guide—he is an essential authority for our time and place, and our deliberations about the future will go better the more widely he is read, for he is offering a deeply informed view on what are quickly becoming the great questions of world politics.”

Robinson’s invention of a new institution, the Ministry for the Future, is precisely the kind of innovation we hope to instigate with the Bold ReThink. We are almost out of time. We need to dedicate as much innovation to governance as we do to technology to get us out of the pickle we are in.

Mckibben again : “This is precisely why one hopes that this book is read widely—that Robinson’s audience, already large, grows by an order of magnitude. Because the point of his books is to fire the imagination, to remind us that the great questions of our lives are not just about love and relationships, but also about politics and economics.”

Will you join us in addressing these great questions? Together we can bend the future.