Why Are Some Communities Less Healthy than Others? Follow the Money

Commentary by Ted Schettler

Social environmental determinants of health (SDOH) largely explain why a newborn girl has a life expectancy of more than 80 years if she is born in some countries but less than 45 years if she is born in others. Or why zip codes in the US accurately predict many measures of individual and community health, including life expectancy. Eco-social environments have greater influence on our health than access to good health care, although in the US we spend far more money on health care for sick people than on disease prevention in populations through eco-social interventions.

Social circumstances, environmental exposures, health behaviors, and health care are the predominant determinants of population health. In reality these categories are not separate but interact and can shape one another. For example, prenatal and early-life social stressors increase the risk of childhood asthma onset as a result of chronic exposure to traffic-related air pollution. And social circumstances can make exposure to traffic-related air pollution more likely. Reliable access to good health care may be challenging for families living in poverty, but it is essential for optimal asthma management. The primary prevention of asthma involves intervening further upstream across a range of social and environmental indicators.

The Centers for Disease Control and World Health Organization (WHO) define the SDOH as the conditions in which people are born, grow, live, work and age. These conditions are mostly shaped, they say, by the distribution of money, power, and other resources at global, national, and local levels. Social determinants of health are largely responsible for health inequities – the unfair and avoidable differences in health status within and between countries—sometimes called the health gap.

In their 2008 report, Closing the Gap, a WHO commission said:

“[Health inequities and the health gap] are caused by the unequal distribution of power, income, goods, and services, globally and nationally, the consequent unfairness in the immediate, visible circumstances of people’s lives – their access to health care, schools, and education, their conditions of work and leisure, their homes, communities, towns, or cities – and their chances of leading a flourishing life. This unequal distribution of health-damaging experiences is not in any sense a ‘natural’ phenomenon but is the result of a toxic combination of poor social policies and programmes, unfair economic arrangements, and bad politics. Together, the structural determinants and conditions of daily life constitute the social determinants of health and are responsible for a major part of health inequities between and within countries.”

The WHO commission made three overarching recommendations with the aim of achieving health equity:

1)Improve daily living conditions; 2) Tackle inequitable distribution of power, money, and resources; and 3) Measure and understand the problem and assess the impact of action

Indicators of the social determinants of health:

Indicators of social factors that influence health have evolved and vary depending on the level of analysis, purpose, and where boundaries are set on sources of data. Here are several examples:

At the individual level, the National Academy of Sciencesidentifies five domains of social risk factors likely to be important to health outcomes of Medicare beneficiaries: 1. Socioeconomic position; 2. Race, ethnicity, and cultural context; 3. Gender; 4. Social relationships; and 5. Residential and community context.

The Area Deprivation Index is based on a combination of income, education, employment and housing quality evaluated at the census block group level throughout the US.

The National Equity Atlas considers a lengthy list of indicators that “track how communities are doing on key measures of inclusive prosperity. [It] defines an equitable community as one where all residents — regardless of their race, nativity, gender, or zip code — are fully able to participate in the community’s economic vitality, contribute to its readiness for the future, and connect to its assets and resources.”

The Opportunity Index uses indicators from the domains of economy, education, health, and community to give a broad picture of opportunity at the state and county level in the US.

Dignity Health (formerly Catholic Healthcare West) developed the Community Need Index to help health care organizations, not-for-profits, and policymakers identify and address barriers to health care access in their communities. The CNI aggregates five socioeconomic indicators long known to contribute to health disparities–income, culture/language, education, housing status, and insurance coverage–and applies them to every zip code in the United States.

County Health Rankings & Roadmaps measures health-related factors in communities around the US to drive change towards improving health. The program provides snapshots of community health as well as a community ranking system. Rankings are based on indicators of health outcomes—length and quality of life—and weighted scores of four health factors: health behaviors, clinical care, social and economic factors, and the physical environment.

A number of the indices and ranking systems give limited attention to physical environmental quality indicators even though many features of a community’s environment are determined by social policies and programs. That has begun to change as community groups repeatedly showed that adverse social and environmental conditions often co-occur and began demanding environmental justice.

The environmental justice movement arose in the early 1980s when it became apparent that hazardous waste facilities were often intentionally located in communities where largely low-income, people of color lived. Since then many grassroots environmental justice organizations have formed throughout the country and internationally in order to push back against the practice of siting pollution sources in already overburdened communities with limited resources, adding more threats to health. The EJ Screen and CalEnviroScreen are examples of tools with more detailed descriptions of environmental features added to the list of indicators of SDOH.

Environmental Justice Screen, EJ Screen:

The US EPA developed a tool called the EJ Screen that includes 11 environmental indicators and 6 demographic indicators. Each environmental indicator at a particular location is combined with a demographic indicator at the same location to derive an environmental justice or EJ index for that particular environmental indicator. The EJ Index is higher in block groups with large numbers of mainly low-income and/or minority residents with a higher environmental indicator value, such as higher levels of hazardous air pollutants or traffic volume. Advocates and decision makers can use this information to identify throughout the US communities in need of particular policy, investment, or programmatic interventions.

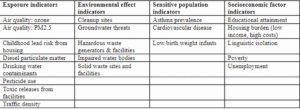

As the result of successful campaigning by EJ groups in CA, the California EPA developed a mapping tool called CalEnviroScreen that helps identify communities most affected by the cumulative impacts of many sources of pollution and where people are especially vulnerable to pollution’s effects. It uses environmental, health, and socioeconomic information, obtained through specific indicators, to produce scores for every census tract in the state. Indicators for the newest version of the tool (v4, draft) are shown in the table below. The aim is to be better able to address the cumulative effects of both pollution burden and additional factors and to identify communities that might need particular policy, investment, or programmatic interventions.

Community and EJ groups can use the data to advocate for environmental cleanups, improved pesticide buffer zones, safer school siting, resisting additional sources of pollution and other purposes. Regulators and legislators are pressured to use this kind of information in their decision making, as recently happened in New Jersey.

As a result of political organizing and advocacy by EJ groups, in August 2020 New Jersey adopted legislation that requires the state Department of Environmental Protection to evaluate the environmental and public health impacts on vulnerable communities when reviewing permit applications for certain new facilities, including:

-

- Major sources of air pollution (i.e., gas fired power plants and cogeneration facilities);

- Resource recovery facilities or incinerators; sludge processing facilities;

- Sewage treatment plants with a capacity of more than 50 million gallons per day;

- Transfer stations or solid waste facilities;

- Recycling facilities that receive at least 100 tons of recyclable material per day;

- Scrap metal facilities;

- Landfills; or

- Medical waste incinerators, except those attendant to hospitals and universities.

An article in the National Law Review describes the bill as the “most far-reaching environmental justice legislation in the country”, requiring an “Environmental Justice Impact Statement” in initial permit applications and permit renewals for covered facilities located in the same census tracts as overburdened communities. The statement must include an evaluation of any potential unavoidable environmental and public health stressors by the facility, as well as any existing environmental and public health stressors already borne by the overburdened community. Under the bill, “overburdened communities” are defined as census tracts with low-income, minority, or non-English speaking populations exceeding specified thresholds.

Looking ahead:

The conditions in which people are born, grow, live, work and age are more complex than described by commonly-used indicators of SDOH. The overlap of environmental justice and SDOH is well-established in an eco-social model of the determinants of health. The model emphasizes interactions of social environmental variables and their influences on health outcomes. Additional theoretical frameworks will help to more fully describe lived-experiences that influence the health of many people not captured by existing models.

“Intersectionality” is a somewhat newer approach gaining traction in epidemiology and having initial impacts in decision making. Intersectionality is a theoretical framework that examines how multiple social identities such as race, gender, sexual orientation, and socioeconomic status intersect to influence individual experience as they reflect societal forms of discrimination such as racism, sexism, heterosexism, and classism. This framework acknowledges that intersections among these forms of discrimination or oppression based on one’s identity can have significant health consequences.

For example, Ami Zota and Bhavna Shamasunder noted that compared with white women, women of color have higher levels of beauty product-related chemicals in their bodies, independent of socioeconomic status. Some of these chemicals have hazardous properties and pose risks to health. The authors proposed that elevated levels are due, in part, to “the environmental injustice of beauty.” The idea is that racism, sexism, and classism intersect to discourage or even penalize Black people, especially Black women, for wearing their hair in natural styles. Now the 2019 CROWN act in CA prohibits discrimination in the workplace based on hair style or texture. Similar laws have been adopted in other states.

The intersectionality framework obviously overlaps with traditional SDOH and EJ considerations. Together they point to the need for more political action. They also show how difficult it is to design studies aimed at revealing the impacts of these multiple, interacting variables.

New methods of data collection and analysis are being developed. For example, multilevel analysis of individual heterogeneity and discriminatory accuracy (MAIHDA) is a novel reorganization of concepts in social epidemiology meant to allow better understanding of the distribution and determinants of individual and population health. In a literature review, Madeleine Scammell concludes that incorporating qualitative methods into environmental health research may improve our understanding of exposures, their pathways, and outcomes, including the influence of social factors.

The concept of the SDOH can be traced to Florence Nightingale who emphasized the importance of the context of where one lived and social networks along with cleanliness, sunlight, and fresh air. Over the past century we have improved our understanding of the SDOH, their interactions, and impacts. We have newer screening tools and growing applications in public policies, although more are needed. But substantial health inequities and the health gap remain. The unequal distribution of power, income, goods, and services that are responsible, noted in the 2008 WHO report, also remain. As the report concludes, they are the result of a toxic combination of poor social policies and programmes, unfair economic arrangements, and bad politics.

Originally published on the Science and Environmental Health Network website.